For three decades, documentary filmmaker Ken Burns has been exploring the people, places, and events that comprise the fabric of America. Whether a bridge over the East River in New York, a five-year war between the states, or the transformative writer of the 19th Century, the driving force at the heart of all of his films has been what he describes as a “deceptively simple” question: Who are we as a people?

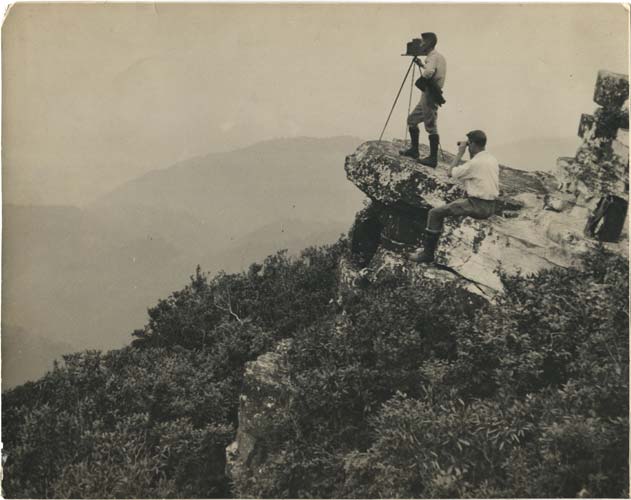

His latest project, “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea,” is a 6-part, 12-hour history of some of the most sacred and spectacular places in our nation, the effort to preserve them in the face of competing interests, and the men and women who struggled to make sure that these lands were, indeed, “our lands.”

Farmers’ Almanac caught up with Burns in advance of the debut of his film to talk about the film, America, history, and more.

FA: For all intents and purposes, your career started out with the story of a single man-made monument, the Brooklyn Bridge. Now your latest project focuses on a collection of monuments, both man made and natural. Do you have a sense that you’ve been building up to this project for a while now?

KB: Oh absolutely, but I don’t think in that direct “monumental” way. I think it’s more that as we have explored this question that animates all of the films that we’ve made–the very deceptively simple question, “Who are we?”; or or or maybe better asked or maybe Who are these strange and complicated people who like to call themselves ‘Americans’?” —we found that an investigation of the past tell us about not only where we’ve been, but where we are and where we’re going (maybe highlight this quote somewhere). We have embraced a number of subjects that could loosely be sort of subdivided into issues of race and issues of space. I think that more often than not, those two great sub-themes of America that reveal in good and bad ways so much about who we are, inter-mix with many of the films we’ve done.

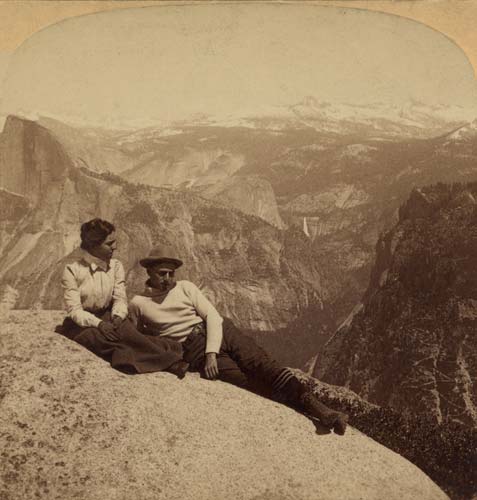

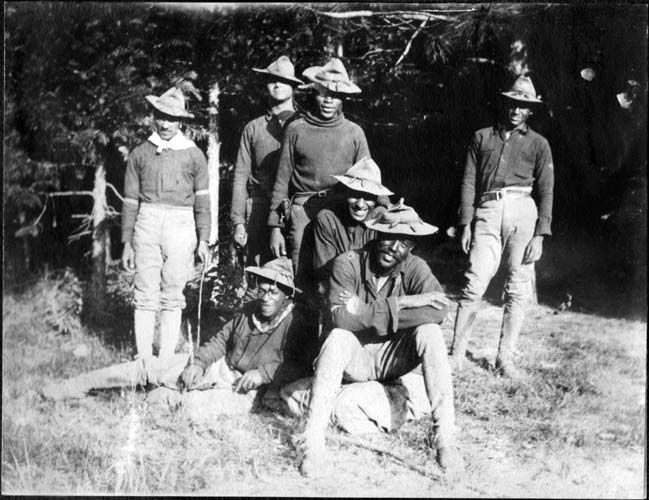

Obviously race has been central to films that we’ve done — The Civil War, Baseball, Jazz, Jack Johnson, Thomas Jefferson. The space of America has certainly been present in our history of The West, and Lewis and Clark, and Horatio’s Drive, and I think it’s reached its apotheosis in this story about the National Parks. For the first time in human history, land was set aside for everybody, not just the rich or the powerful. That is in itself a powerful American story. The National Parks are the Declaration of Independence applied to the landscape.

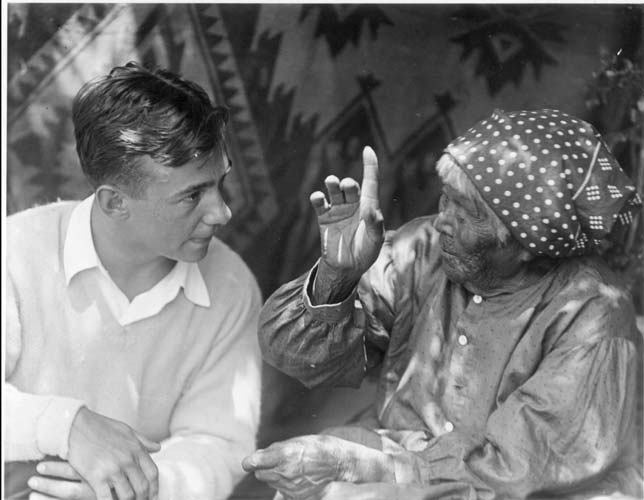

When we talk about parks in general, our relationship is one in a natural or travelogue sense rather than a historical one. How do they come into being? Who are the people responsible for preserving these places? What were the obstacles that those people who wished to set aside these lands faced as America with its great acquisitive and extractive energies was barreling through those landscapes? Who are the unsung heroes? We know that it’s not just John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt, and our film introduces people to literally dozens of folks — black, brown, red, yellow, as well as white — who are as responsible for the parks as anyone.

FA: Why was it more moving than you thought it was going to be?

KB: I’ve done films on the Civil War and the Second World War and those have engendered copious amounts of tears among the viewers. We’ve been seeing in screenings the same amount in The National Parks. These tears come from a couple of different levels: the parks attract us in a deeply spiritual way; they are a place where so many of us have had a transformative moment; where we had our sense of place in the universe confirmed, or at least we were awakened to. But it’s also about the intimate transmissions, as the historian William Cronon describes in our film, where we’re taken by our parents, then we take our kids; we are perpetuating some incredibly important, not only American, but intensely personal stories. So we have these spiritual, “experiences” where we are faced with nature, where we have a sense of human beings not cut off from the landscape but connected to it. All of these feelings or experiences conspire in a way that we weren’t quite prepared for, a kind of cocktail of emotions that really have knocked us–first as the filmmakers, and then audiences as we’ve shared it around the country–sort of out of the comfort zone into this emotional place. It’s not a discomfort zone, it’s pleasing emotions, but it’s nonetheless very powerful and we had no idea we were getting into that as we began the project ten years ago.

FA: When and why did the notion to pursue this project first hit you?

KB: Dayton Duncan, who is the co-producer and writer of the series, came to me ten years ago with the idea. He had come to me in the past with ideas that took awhile for me to buy into. As such, Duncan thought I’d be reluctant to get into this new adventure he had. But since we both had been out in the American west, it didn’t take much for me to realize that the story of the National Parks is the story of America in every sense. This was a story that hadn’t been told yet.

Most people think American history is the history of the presidency, punctuated by some dramatic wars, but it is of course in following that narrative you miss so much of what the country is about. The bottom-up stories of so-called “ordinary people,” all the various sub-themes and undertows that often are ignored by that sort of lofty Pantheon of “great white presidents” and now one black president. So we’ve been hard at work at a different kind of history and The National Parks, as Dayton presented it to me, took all of 30 seconds to reply “You betchya!”

FA: The debut of this film comes at a time where there seems to be a greater collective interest in, and understanding of, both historic and environmental preservation in the United States. Do you think this awareness makes this a better time than, say, 15 years ago, to come out with a film about the National Parks?

KB: It’s hard to say because it is what it is. I think we are more environmentally sensitive, and I think that particularly in tough economic times, the parks have, paradoxically, had great increases in their attendance. I think you’re made to feel more American, more connected to each other. One of the things the parks do is appeal to that spirit. The first Director of the National Parks Service, a man named Stephen Mather, called them, “Vast school rooms of Americanism.” Beyond whatever intimate, spiritual or — whatever you want to call it — “rapturous” moments that you can have, whatever personal connections you forge with your family and the generations of your family, you also have a possibility of coming together as Americans, and indeed as citizens of the world. We’re thrilled about that.

I think we’re at a moment when reminding people of the treasures that we own in common, particularly in an economic crisis, where it might be pleasing to realize how rich we actually are; that you and I own some of the most spectacular ocean-front property; that you and I own, together, some of the most amazing mountain ranges; the highest free-falling waterfalls on the continent; the most spectacular collection of geothermal features on Earth; and the grandest canyon in the world — that we own these together. And that all our ownership might require is that we visit our property now and then, that we make sure there’s proper maintenance, and that we put it in our will for our kids. It’s a great bargain.

FA: The relationship with the land that you mentioned earlier — do you think that’s in some ways connected to the notion of small town life in America, or rural life?

KB: Oh, very much so. I think there is an intimacy that takes place in a small town that you can’t find anywhere else, which I particularly enjoy. It’s so interesting to see that cities themselves naturally divide through some sort of preservationist mitosis into neighborhoods. And then you begin to replicate in those neighborhoods the same kind of relationships you’d find in a small city or town. You buy your paper from the same vendor, you get your bagel at the same place — people forge those intimate connections. But the larger anonymity of the city always threatens to intrude on those personal relationships. Whereas in a small town, the manners and the society are more entrenched, and that’s hugely important to me. I love the energy of cities, but I think there’s even more energy, as we’ve been speaking in this whole conversation, to be had in nature. That’s what the genius of the National Parks is: the restorative refuge, oases that they represent.

FA: What effect do the parks have on the sense of identity of the nearby communities?

KB: Well it’s interesting because the parks represent at once this great paradox at so many levels — obviously there’s this intimate paradox that you stand on the rim of the Grand Canyon and you feel you’re insignificant, but yet somehow that makes you feel bigger. So there’s that paradox. There’s the other paradox that the National Parks grapples with all the time, which is they have to preserve their land for the enjoyment and benefit of the people, but they also have to leave it unimpaired for future generations. This presents the questions “Is it possible to wear out the scenery or love a place to death? And the answer is obviously, yes.”

The larger paradox is that of course Americans believe, quite rightfully, that decisions they make at the local level should be the right decisions. But every once in a while, the “us of us” — that is the Federal — has to make a decision. We don’t really complain when an Air Force base goes up nearby, but we have traditionally resisted our National Parks at a local level, and then embraced them whole-heartedly as the sting of whatever concession to the Federal Government wears off. So when Theodore Roosevelt designated the Grand Canyon as a national monument, and later a national park, it was fought tooth and nail by the citizens of Arizona and specifically, those in Coconino County where the Grand Canyon happens to fall. And it’s a dramatic story that we tell in our film, and that’s part of the dynamic.

The early National Parks had to be described to Congress as “worthless property.” When you think of Yosemite or Yellowstone being described to the Congress of the United States of America as “worthless,” that means there’s something going on there in which we’ve got to convince those people — those acquisitive and extractive interests, and some might even say rapacious interests — that always sees a river and wants to put a dam, looks at a beautiful canyon and thinks “mine,” sees a stand of timber and thinks “board feet,” that this might actually be a good thing to save for our posterity before we run out of it. And of course, because we did that, we’ve also not run out of animals. We wouldn’t have any Bison in the United States if there hadn’t been a Yellowstone National Park. We detail, very dramatically I think, some of the local, initial resistance, despite local interest in creating the parks — it’s always not the “top-down” story, it’s not the benevolence of some politician or some Congress; the story of every National Park is the story of someone local who fell in love with the place and devoted their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor to seeing them achieved.

FA: What are some of the ways that long-form documentary can withstand the short-attention-span, on-demand, YouTube, iPod culture of modern media?

KB: It’s so funny — it’s there and we can lament and wring our hands as we do about this erosion of our attention and it’s true. But still, the highest-rated program on PBS in the last dozen years was our World War II film two years ago; the highest-rated program ever is our Civil War series; the most-watched is the Baseball series. You’re talking about tens of millions of people who are willing to submit to, respectively, fifteen hours, eleven-and-a-half hours, and eighteen hours of The War, The Civil War, and Baseball. That’s amazing. Every time a “Harry Potter” book comes out, the kids lineup the midnight before and they snatch up tens of millions of copies of a book that will take them much longer than any of those films to read, right? And that just shows you that despite all of the technological tendency to reduce something to some knowing, but essentially vacuous, 40 seconds of understanding — which is no understanding at all — we still yearn for those long-forms. So I’ve been like the rock around which the current is breaking. I might be polished around the edges but I’m still there.

FA: Do you think in some ways that there’s a little bit of a “Darwinian effect” here? That what the short-attention-span culture does is really test to see if the long-form stuff, like books and like documentary film, if they’re really good people will still put down the iPod and put down the cell phone?

KB: I think there is and I think there’s another Darwinian effect among those who are too lazy to submit to longer forms, which is they put themselves in peril. And I think we’re seeing this in the tough economic times. If you’re so ‘dumbed-down’ that you don’t think because you get everything from YouTube, or from Facebook or just checking out the abbreviated news, if that at all, that you think you could know what’s going on? “The only thing that’s really new,” Harry Truman said, “is the history you don’t know.” And you’re going to find a lot of people shedding some of this frivolousness in favor of something with more dimension as this economic crisis deepens.

FA: In all your years of field production, what’s the worst weather you ever encountered?

KB: We had wind chills of 60 below in the Dakotas filming Lewis and Clark, and I’ve been in places in the Grand Canyon where I couldn’t sleep, it was 3 A.M., and the rock next to me was still hot to the touch; it was radiating 110, 115 degrees, even at 3 in the morning. So those are the extremes. But can I tell you something? We were loving every second of it!

FA: Any favorite sunrise or sunset on a shoot?

KB: Well as Dayton wrote before we worked together, he was a journalist and he wrote an article for the Boston Globe Sunday Magazine once in the mid-eighties and did an article on me and a film I had coming out at that time on the history of the Congress, and he said that I’d, “seen more dawns than a milkman.” I thought it was a great way of describing what we do in our line of business. So, like your own children, there have been so many different places that I’ve been — in Denali, at Yosemite, at the edge of the Brooklyn Bridge, on the rim of the Grand Canyon, at Gettysburg, at Antietam — that have been special to me, that to compare them or to rate them devalues the whole process of getting out into them.