There’s a lot to see in the sky during these nights and early mornings in September, including a full Harvest Moon and stunning planetary pairings. Mark your calendars!

All times are listed as Eastern Daylight Time for the Northern Hemisphere.

Take note that we sometimes will use angular degrees to define the separation between two objects, such as (for example) the Moon and a bright planet. Keep in mind that the width of your clenched fist, held at arm’s length, measures roughly 10°.

When we speak of magnitude, we are referring to the brightness of an object; the lower the figure of magnitude, the brighter the object. The brightest stars are zero and first magnitude. Under a dark, clear sky, the faintest objects that you can see with just your eyes are fifth or sixth magnitude. Objects with negative magnitudes are the brightest. Sirius, the brightest star, is -1.4. Venus can get as bright as -4.8. A Full Moon is -12.7 and the Sun is a blindingly bright -26.7.

September 1 – The only planet that is completely out of view for this entire month is Mars. Still an evening object, it simply is too faint and too close to the Sun to be seen. It will transition to the morning sky early next month, but we’ll have to wait until the last week of November until it finally begins to emerge from the bright twilight.

September 5—Venus which has been languishing low in the dusk all summer, at last, manages to stay above the west-southwest horizon as late as the end of evening twilight. This evening, the Goddess of Love (magnitude -4.0) makes a beautiful passage by the 1st-magnitude star Spica; look for Spica less than 2° to Venus’s lower left. Tomorrow evening you’ll find it 2° to Venus’s lower right.

September 6—New Moon at 8:51 p.m. In this phase, the Moon is not illuminated by direct sunlight and is completely invisible to the naked eye.

September 9—This evening, a three-day-old crescent Moon sits about 4½° to the upper right of Venus. About 5° below both, you’ll perhaps still see Spica (binoculars will help). All three objects, Moon, planet, and star, will form a large, loose triangle, visible low in the west-southwest sky about 40 minutes after sunset. In telescopes, Venus still appears rather unimpressive, displaying a rather small gibbous disk, 70-percent illuminated by the Sun.

September 13—First Quarter Moon at 4:39 p.m. In this phase, the Moon looks like a half-Moon in the sky. One-half of the Moon is illuminated by direct sunlight while the illuminated part is increasing, on its way to becoming a full Moon.

September 14—Mercury reaches its greatest elongation today. Although 27° east of the Sun, it is also well to the south of it and may briefly be visible with binoculars before it sets only ¾ hour after sundown from mid-northern latitudes. Observers in the Gulf Coast states and the Desert Southwest are more favorably located to see this zero-magnitude planet as it follows the Sun by an hour during the first half of the month.

September 16—Facing due south at 10 p.m. local daylight time, you’ll see the waxing gibbous Moon and located nearly 5° directly above it, shining with a steady, yellow-white glow is the planet Saturn (magnitude +0.4). In the 2021 edition of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s Observer’s Handbook, planet editor Murray Paulson notes that “With its incredible system of rings, Saturn is possibly the most spectacular object in the Solar System, and are visible even in steadied (or image-stabilized) high powered binoculars and small spotting scopes.”

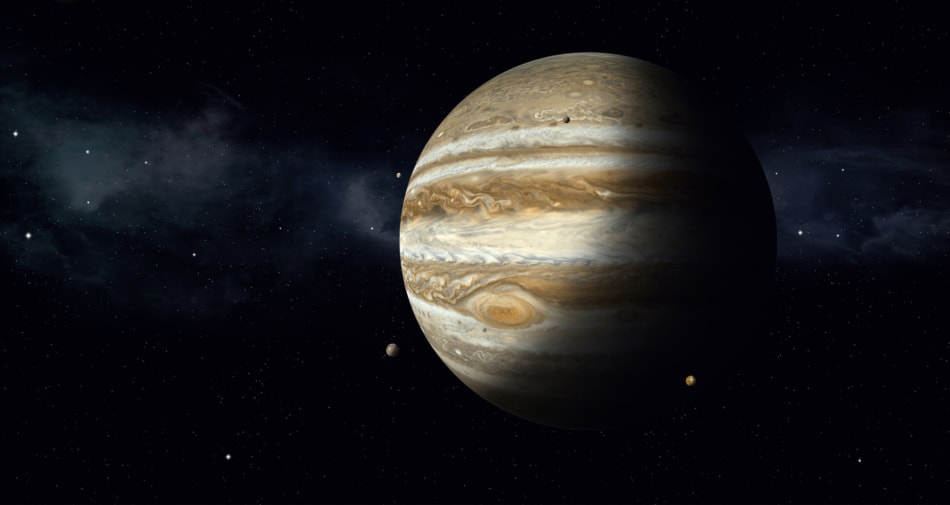

September 17—This evening, it is brilliant Jupiter’s turn to be visited by the Moon. At magnitude -2.8, this big planet shines 19 times brighter than Saturn. Despite the fact that it is five times Earth’s distance from the Sun, Jupiter’s giant size and reflective clouds make it a celestial beacon that is unmistakable. Jupiter and the Moon appear due south at around 10:50 p.m. local daylight time, with Jupiter standing nearly 6° to the upper left of the Moon. The orientation will have noticeably changed a couple of hours later, with Jupiter standing directly above the Moon and about a degree closer to it. The smallest of telescopes will reveal Jupiter’s four large moons, each of which is equal to or larger than our own. They provide a never-ending fascination for amateur astronomers.

September 20 – Full Harvest Moon at 7:54 p.m. But wait! It’s not autumn yet! Usually, we think of the Harvest Moon as the first full Moon of the autumn season, but the “Harvest Moon” is actually assigned to the full Moon closest to the autumnal equinox, which, in this case, will occur about 1.8-days later. The ecliptic-horizon angle at this full Moon makes the daily delay in moonrise less than the 50-minute average. From latitude 40° north, for example, over the next three nights, the average difference is only about 23 minutes. Read more about the “Summer Harvest Moon” here.

See our full Moon dates and times for the year here!

September 22—First Day of Fall at 3:21 p.m. with the arrival of the autumnal equinox. At this moment, the Sun crosses the celestial equator from north to south. Autumn begins in the northern hemisphere and spring begins in the southern hemisphere.

September 28—Last Quarter Moon at 9:57 p.m. In this phase, the Moon appears as a half Moon due to the direct sunlight, the illuminated part is decreasing toward the new Moon phase.

Compiled by contributing astronomer, Joe Rao. Our schedule is adapted from “Skylog,” a regular feature appearing in Natural History magazine, written by Mr. Rao since 1995.